Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn a series of letters from African journalists, novelist and journalist Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani reflects on the biggest challenges facing Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, as it marks 60 years of independence from Britain.

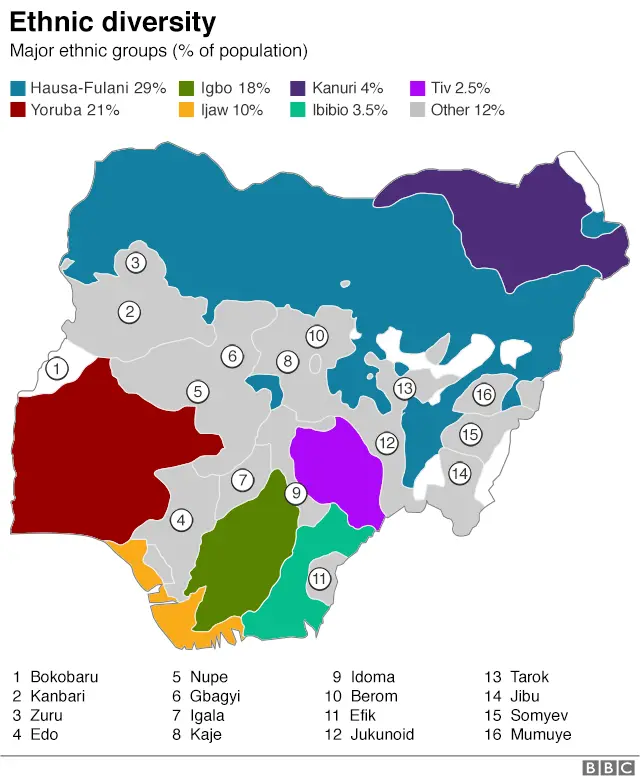

How do we keep the numerous ethnic groups united and happy? This was the biggest hurdle Nigeria faced in the first decade of independence and continues to be so 60 years later.

Heated national conversations usually revolve around which ethnic group gets what, when, and how. Or how fairly people in one group were treated compared to people in another group.

A major policy to promote institutional equality was launched by the Nigerian government almost 40 years ago, but it led to further divisions and conflicts.

Nigeria has over 300 ethnic groups, of which there are three major ethnic groups. The Igbo people of the southeast, the Yoruba people of the southwest, and the Hausa people of the north.

These groups were separate entities until Britain united them into one country, but today they operate as a federal system, with power concentrated at the center and distributed across 36 states and the capital, Abuja.

Struggles for central power and concerns about unjust treatment have at various times led to violent conflicts, including pogroms, protests, and the 1967-1970 civil war sparked by attempts by the Igbo people to break away and form a new state called Biafra.

To promote inclusion, the “Federal Personhood Principle” was enshrined in Nigeria’s 1979 Constitution.

It includes a provision for public institutions to reflect the “linguistic, ethnic, religious and geographical diversity of Nigeria”.

Initially, this seemed to appease all regions of the country.

educational disparity

But today, it is one of the most controversial government policies, with many Nigerians complaining that the policy has done more harm than good to our country.

Local newspapers regularly publish headlines such as “Federal character is Nigeria’s curse” and “Groups calling for end to federal character.”

First of all, the “federal character” was not accompanied by a strategy to end the huge educational gap that had always existed between the Muslim-majority northern part of Nigeria and the Christian-majority Nigeria.

This disparity is the result of a complex combination of factors, including religion, culture, past colonial policies, and, more recently, the Boko Haram insurgency.

As a result, the region has the lowest literacy rate in Nigeria, at just 8% in some states.

However, this same region still has to meet public sector capacity. It is quite large, with 90 million people out of Nigeria’s population of 200 million, and 20 states (19 out of 36 states plus Abuja).

“Unfortunately, the term ‘federal character’ has become a euphemism for recruiting unqualified people into the civil service,” said Ike Ekweremadu, former deputy president of the Nigerian Senate.

“These workers reduce productivity, weaken public services and ultimately make them inefficient.”

“Federal character” also applies when reaching senior positions in public institutions, making it easier for these unqualified people to rise above their more qualified colleagues.

Additionally, ethnic conflicts often cause people to try to uplift as many of their relatives as possible when they find themselves in a position to do so.

Northerners have ruled the country for 38 of Nigeria’s 60 years of independence, primarily through military coups.

I have heard bitter stories of many Nigerians who worked hard for no reward while some of their colleagues were just plodding along on the path to promotion because their relatives were in power.

Because of its “federal character,” ethnic unity and striving for positions of authority tend to take precedence over self-improvement and excellence.

Almost every year, the announcement of the cut-off marks for admissions into Nigeria’s top public secondary schools is followed by heated social media posts, newspaper columns and parliamentary debates.

Students from some states in northern Nigeria may require scores as low as 2 out of 200 for admission, while students from southern states require at least 139 points.

“We have the best team”

And because the “federal character” requires each state to have a representative in the president’s cabinet, merit and excellence are often sacrificed for diversity when appointing department heads.

With so much talent in Nigeria, many of Nigeria’s brightest minds do not get the opportunity to take the country forward by neglecting their knowledge and skills.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Nigeria won the U-17 World Cup for the fifth time in 2015, critics of its “federal character” were quick to point out the lack of diversity in the national team.

Nigeria just went into the tournament giving their all.

Before the match, national coach Emmanuel Amuneke was criticized for including players in his squad that were clearly from the south-east.

You may also be interested in:

He was forced to explain that he simply chose what he thought was the best, without paying attention to the origin.

Some Nigerians argue that a “federal character” is essential to national unity and that some adjustments are needed to make it work.

Qualified people exist in every region, so all you have to do is find them.

After all, some of Nigeria’s top globally recognized minds in many fields come from the educationally disadvantaged north.

“But every Nigerian has to be a competent person. There should be a merit test, a competency test.”

Power politics in Nigeria:

President Muhammadu Buhari has also been frequently maligned by those opposed to “federal character” as he appears to have abandoned this policy.

“There is no problem with any region in Nigeria, but there is a problem with the way the government directs appointments,” Ekweremadu said during intense parliamentary deliberations in 2018.

Currently, 17 of the 20 Nigerian military chiefs appointed by Buhari are from the northern region, and 16 are Muslims like Buhari.

Of the 21 police inspectors, 15 are from the north and 16 are Muslims.

Presidential Spokesperson Garba Shehu defended his boss, telling me: “Are you willing to hand over the position of military commander to someone you don’t trust?”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFormer President Olusegun Obasanjo, once a supporter of Buhari, recently accused him of “mismanaging diversity” and being responsible for Nigeria being more divided today than ever before in its history.

Nobel laureate and author Wole Soyinka shared a similar view last month, referring to a “culture of sectarian privilege and dominance.”

But Buhari’s spokesperson pointed out that previous administrations had faced similar accusations.

“When you’re not at the[government]seat, you’re always watching other people do wrong,” Shehu said.

“When Obasanjo was in that position, he was also accused of appointing people from the South-West.”

Some extremists in the south now believe the only solution is for Nigeria to break up and each major ethnic region to become its own country.

Some politicians and experts favor a “restructuring” that would give each region more autonomy, which would keep Nigeria united but significantly reduce central power.

Whatever Nigeria ultimately decides to do as it celebrates 70 years of independence, one thing is certain: the country’s future depends on how well the next government can maintain unity in diversity.

Other letters from Africa: