Africa’s creator economy is booming and is predicted to grow to $17.84 billion by 2030. However, the vast majority of talented creators are completely ignored by major institutional investors. According to a new report, only 4.2% have actually secured such large, formal funding, and 95% are still waiting for a real investor.

Why do large-scale disconnections occur?

According to the Africa Creator Economy Report 2.0, published by Communiqué and TM Global, the biggest hurdles are fundamental, with most creators simply not having the formal business structures investors seek, and even finding it difficult to raise adequate funding. The report, which primarily surveys creators in leading markets such as Nigeria and South Africa, clearly shows that for many, content creation remains a side hustle and not a large-scale business.

Platform usage in our sample shows that 77% cite Instagram as their primary platform, 56% TikTok, 42% YouTube, and 76% use multiple platforms to make money.

Money problems are real. More than half of respondents have never received external funding, and a large majority (60%) are not looking for funding, mainly because they feel excluded from investors. When they do get cash, it is from informal sources, highlighting the informal nature of the ecosystem. However, 79% recognize that government grants and awards are an available source of funding.

No structure, no investors.

The report argues that many creators lack the structure investors seek, such as business transparency and the potential for scale. Around 40% consider creative work to be a part-time job, and 71% say business strategy and management skills are essential to attracting investment. A further 40% believe business skills training is key to sustainability.

This informal family and friend-based funding system is what is holding the ecosystem back. Speaking at a business day panel at the Africa Creators Summit in Lagos, Marie Lola Mungai asked why creators with millions of subscribers rarely attract institutional investors. She pointed out that even creative economy knowledgeable audiences often struggle to understand the gap between large followings and investability.

Walter Badoo of 4DX Ventures responded that creators are fundamentally a talent class, not a business. “It becomes a business when you encompass IP, systems, infrastructure, etc. in a way that allows you to repeatedly create, deliver, and capture value,” he said. He pointed out that a major risk is the volatility of income, as it is not sustainable and investors will apply a discount. Additional barriers include key personnel risk, opaque intellectual property rights and management structures, and the frequent lack of world-class teams, systems, processes, and governance needed to scale.

David I. Adeleke, Founder and CEO of Communiqué, wrote in the report’s message that Africa’s creator economy is still in its infancy, with creators managing on their own with a system that marginalizes them. Investors are struggling with an ecosystem that is culturally rich but commercially ambiguous, he said.

The report raises questions about whether the creator boom is being glorified or building real economic viability. This suggests that creators need to move from hobbyists to entrepreneurs and formalize their operations to appeal to capital.

The interviews in the report illustrate these challenges. Nigerian pediatrician and content creator Ayodele Renner talks about funding the facility. He says this works well for creators focused on social impact, such as health education, but it comes with scrutiny that can limit creativity. “Creative license is limited because the institution can tell you what they want you to create,” he explains.

Renner has launched ventures such as Agnosis Care on Demand, a home vaccination health tech company, and The Baby Convention, a parenting event. His career as a creator provided the visibility and community that helped launch these. However, he points out that unless the company diversifies into books, courses, consulting, etc., content alone will not be sustainable.

Also read: How Samuel Lasisi is building Conectr to solve the collapse of Africa’s creator economy

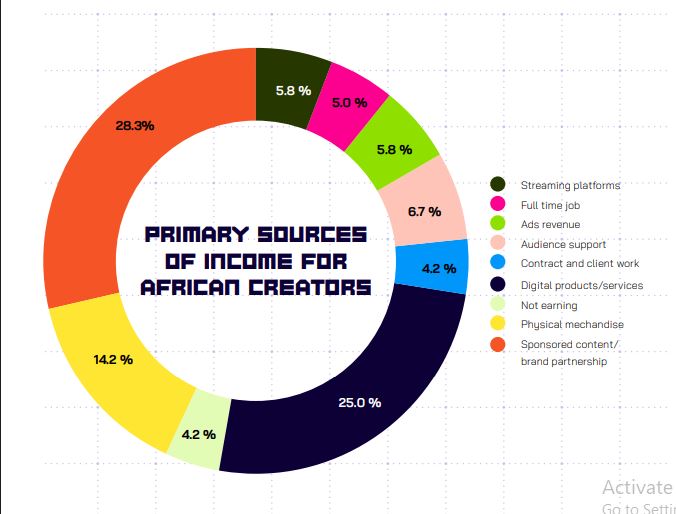

In Nigeria, where the most research has been done, creators like Renner are highlighting the possibilities. The report’s key findings show that 55.8% have less than 10,000 followers and 6 in 10 have a monthly income of less than $100. However, high earners rely 29% on product sales, 28% on brand sponsorships, and 11% on platform payments.

Fanuel Masamaki, a Tanzanian comedian known for his soccer content, says local creators are facing economic limitations. “It’s all about finances. Sometimes the resources we have limit our creativity,” he says. He looked into institutional funding, but couldn’t find one that was ready. He suggests financial support for logistics, campaign links and production equipment.

Masamaki believes Tanzanian creators are ready to invest, citing the increasing quality of content despite the language barrier. The Swahili-speaking community offers a large market, he added.

Also read: Facebook unveils creator tools at Pan-African summit

The report links investment potential to growth stage and says micro-creators need education and guidance. Financial literacy and contracts are necessary for the mid-level workforce. Leading companies seek capital to expand.

In conclusion, the report calls on stakeholders to support the transition. Experts like Marie argue that creators need to build financial discipline. Investors view companies as businesses and adopt the framework, and policy makers enable employment and IP policies.